Black

Inventors

Inquiry

A Critical Inquiry Lesson developed

by Alexander Pittman, Dan Krutka, & Danetra King

This page includes the blueprint for an Inquiry Design Model (IDM) social studies unit designed for anyone—including students from elementary to higher education—who would like to inquire into Black invention. The IDM is well suited for the integration of science activities. Teachers can learn more by reading the article linked below.

Teacher Resources

A Humanizing Approach to Teaching Black Inventors

In his opinion piece, Ezelle Sanford III argues that although the way history remembers Black inventors has changed over time, it still often falls short by focusing too narrowly on inventions instead of full human lives. Early efforts, such as Carter G. Woodson’s creation of Negro History Week, emphasized patents and technological achievements to fight racist claims of Black inferiority during Jim Crow. Later, during the civil rights era, fuller biographies of figures like George Washington Carver were used to inspire pride and resilience. Today, however, Sanford argues that internet lists and simplified stories again reduce Black inventors to names and products, stripping away context, struggle, and identity. He points to newer works such as Hidden Figures and The Immortal Life of Henrietta Lacks as better models because they show inventors as complex people shaped by race, gender, sexuality, and history. Sanford concludes that truly honoring Black inventors requires understanding their lives, not just counting their inventions. This aligns with scholarship, namely Rayvon Fouché’s book and LaGarrett King’s approach to Black Historical Consciousness, that has informed our approach. This inquiry curriculum aims to tell about the full lives of Black inventors, not reduce them to their inventions.

Technoskeptical Practice

Scholars at the Civics of Technology project contend that technology is too often only understood for its intended purpose and benefits (Krutka et al., 2022). Cultivating a technoskeptical outlook encourages students to suspend their judgment and critically inquire into not just benefits, but also unintended, collateral, and disproportionate effects of technological change. In the realm of Black invention, this is illustrated by how, for example, Black computer scientists such as Joy Buolamwini and Timnit Gebru have challenged the racial bias and harms of AI technologies. Educators can view technoskeptical frameworks and questions on our Curriculum page.

Example Standards

Add here.

Glossary

Invention (en-vin-shun)

The act of bringing ideas or objects together in a novel way to create something that did not exist before.

Source: Britannica.com

Enslaved People (In-SLAYV-d)

An enslaved person is someone whose is forced to work for and obey an enslaver and is considered to be their property. These words are preferred because they show that enslavement is imposed on people, not who they are; And enslavers actively uphold violent oppression of other human beings.

Patent (PAT-uhnt)

A legal document giving someone the sole rights to make or sell a product

Source: “Lewis Latimer: The Man Behind a Better Light Bulb” by Nancy Dickman

Segregation (Seg-ri-GAE-Shun)

Segregation is the practice of requiring separate housing, education and other services for people of color. Segregation was made law in many places in the 19th- and 20th-century U.S. as white people often believed racist ideas and sought to maintain their economic power.

Source: History.com

Black Joy

Black Joy is finding the positive nourishment within self and others that is a safe and healing place. It is a way of resting the body, mind, and spirit in response to the traumatic, devastating and life-altering racialized experiences that Black people continue to encounter.

Source: National Museum of African American History & Culture

Compelling Question

What lessons should we learn from the lives of Black inventors?

Staging the Question

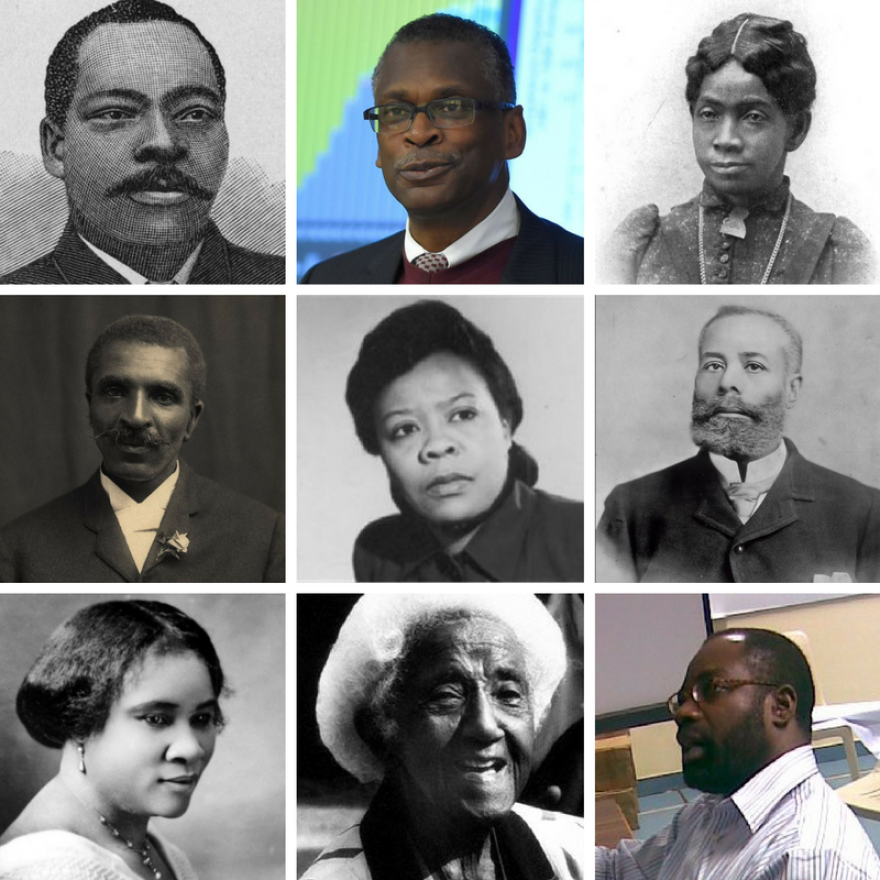

George Washington Murray (1853-1926)

Henry E. Baker (1857-1928)

Teachers can open the lesson by asking students, what inventors do you know of? After discussion the teacher could ask, what inventions do you know of that were invented by Black people? After a short discussion, the teacher then shares the stories of Henry E. Baker and George Washington Murray with students. They can do so by either assigning them to read “Found on Baker’s List” or read this shorter version:

In 1894, a man named George Washington Murray stood in the U.S. Congress and read aloud a list of inventions made by African Americans. At the time, he was the only Black member in either body of the U.S. Congress. The list showed inventions like farm tools, machines, and everyday objects. It was created by Henry E. Baker, who worked at the U.S. Patent Office. Baker wanted to prove that Black inventors were creative, skilled, and important to the country, even though many people wrongly said they were not because of their race. He spent years conducting research and sending letters to develop what became known as “Baker’s List.”

George Washington Murray was once enslaved, but he became a farmer, teacher, inventor, and politician. He created farm tools to help small farmers work more easily. Henry Baker faced racism too, but he spent many years conducting research and sending letters so he could accurately record the names of Black inventors at a time when no official records catalogued that information. Together, their work helped protect these inventors from being forgotten. One legacy of their work is that there is a long tradition of teaching Black inventors in schools, particularly during Black History Month.

Supporting Question

Why do African inventions of the past still matter?

African inventors of the past and present

Short Bio: African inventors and innovators have shaped human history for thousands of years, yet their contributions are often overlooked or minimized in traditional accounts of science and technology. Long before modern Europe, African societies developed complex systems of knowledge, craftsmanship, and problem-solving that responded to local environments, social needs, and cultural values. These inventions were not isolated achievements. They were part of rich technological traditions that included ceramic production for cooking and storage, advanced metalworking, large-scale architecture, medical knowledge, and artistic design.

In early African civilizations, invention and innovation emerged across generations. Pottery developed independently in multiple regions of Africa, including the Central Sahara, the Nile Valley, and West Africa. These ceramic technologies reshaped how communities prepared food, managed resources, and organized daily life. Metalworking traditions produced tools, weapons, and artworks that required advanced technical knowledge. Ironworking and the lost-wax bronze casting technique were used to create the famous Benin Bronzes and metal objects from the Niger River region. These technologies supported trade networks and cultural expression across the continent.

Examining African inventions helps reveal how power, racism, and culture influence what counts as “technology” and who is recognized as an inventor. From ancient ceramic and metal technologies to modern innovations like Arthur Zang’s Cardio-Pad, African inventors have continued to design creative solutions to real-world problems. Studying these stories challenges narrow narratives of technological progress and highlights how invention is deeply connected to community, context, and human need.

Supporting Question

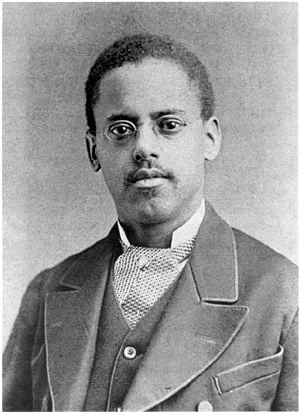

Why does Lewis Latimer’s story still matter?

Lewis H. Latimer (1848-1928)

Short Bio: Lewis Howard Latimer (1848–1928) was an inventor and draftsman who is most known for helping to bring electric light to more people. He was born in Chelsea, Massachusetts. His parents escaped slavery and their enslaver sought to recapture his father, George. A movement that included abolitionists William Lloyd Garrison and Frederick Douglass helped to secure his freedom even though he feared that he could be forced back into slavery. As a teenager, Latimer joined the U.S. Navy during the Civil War. After the war, he worked at a patent law office for little pay. He learned drafting skills, which means making careful technical drawings. Despite the racism of the time that often limited job opportunities, Latimer’s skill eventually earned him a job as a draftsman. He kept going and used his skills to open doors that many people tried to keep closed.

Latimer became famous for invention and problem-solving. He helped draw the patent plans for Alexander Graham Bell’s telephone. He also improved parts of electric lighting by creating a better way to make carbon filaments, which helped light bulbs last longer and break less during manufacturing. Many people were working on electric lights at the time, including Thomas Edison and other companies that competed to make lighting safer and more reliable. Latimer worked for Edison’s electric company and later became the first person of color in the Edison Pioneers. Even though he did important work, he did not always receive the same recognition or opportunities as white inventors. Still, he earned respect as an expert and wrote a major book about electric lighting. He also cared about fairness and community. He taught immigrants, supported civil rights, and used his education to help others. Latimer’s life shows how creativity and persistence can challenge bias and help improve society.

Supporting Question

Why does Elijah McCoy’s story still matter?

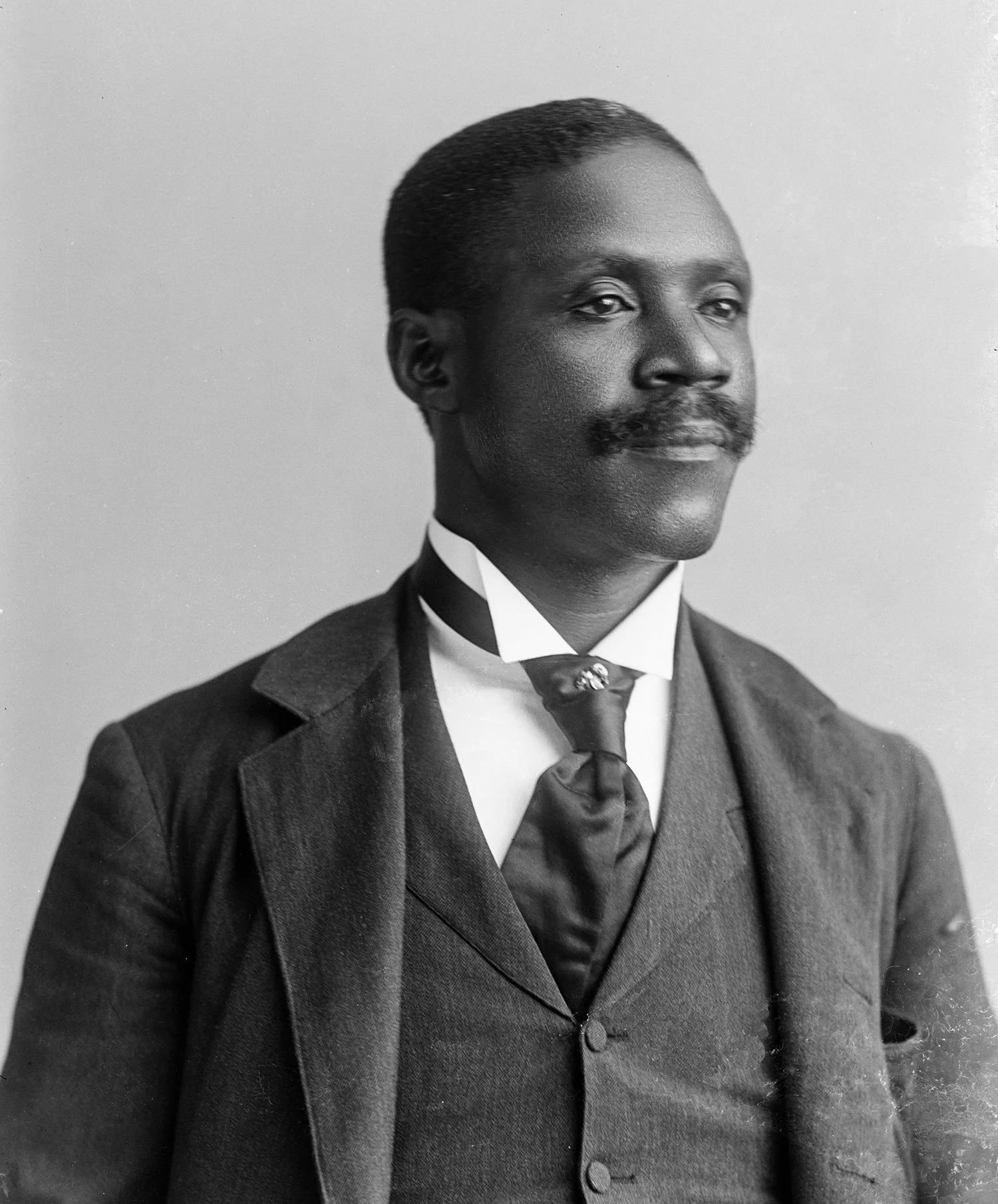

Elijah McCoy (1844-1929)

Short Bio: Elijah J. McCoy (1844 - 1929) is credited with inventing an automatic engine lubrication system for steam engines. This invention saved time and money as it lessened the number of times operators would have to stop. Prior to his invention, engines could only be lubricated while stopped, but his invention offered a way to lubricate the engines without stopping the train. As a child, McCoy showed interest in mechanics. After 15 years in Colchester, Ontario, where his mother and father had settled after fleeing enslavement in Kentucky, McCoy's family sent him to Scotland, to study mechanical engineering at the University of Edinburgh. When he returned to the U.S. as a "master mechanic and engineer," his family had relocated to Michigan.

Once in Michigan, despite his prior achievements, McCoy still faced racism when attempting to find a job. He was eventually able to find work as a fireman and oiler at the Michigan Central Railroad. It was in this position that McCoy spotted the issue of trains having to stop and start in order to lubricate the engine. He used his skills and education to create a solution. In 1872, McCoy patented his invention. His invention became popular among railroad engineers. Though many created their own versions, it is stated that the saying "the real McCoy" references engineers discussing his design of the oil-drip cup. At the time of his passing in 1929, McCoy held more than 50 U.S. patents, and in 2012, the Elijah J. McCoy Midwest Regional Patent Office (the first satellite office of the United States Patent and Trademark Office) was named in his honor. It is important to note that though McCoy held multiple patents, as a Black man with little capital, he often credited his employers of other inventors on his patents in order to be able to produce them. However, later in his career, he created the Elijah McCoy Manufacturing Company where he was able to produce his lubricators and more patented devices.

Supporting Question

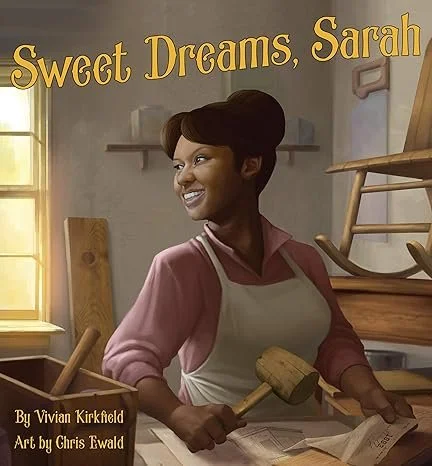

Why does Madam C.J Walker’s story still matter?

Madam C.J. Walker (1867-1919)

Short Bio: Madam C.J. Walker is known for revolutionizing the Black hair care industry. Born as Sarah Breedlove, Walker was born December 23rd, 1867. One of six children, Breedlove was born free to two formerly enslaved parents. After the passing of her parents, Walker was orphaned at the age of seven. She later moved in with her older sister, but experienced abuse from her brother in-law. At the age of 14, Walker married her first husband, who passed away in 1887. From that marriage, she had her daughter, A'Lelia. In 1888, she and “Leila” moved to St. Louis, where she worked as a laundress in order to provide her daughter with a formal education.

Around 1904, Walker became a sales agent for Annie Turnbo Malone, who later became a competitor. However, in 1905, Walker moved to Denver, Colorado where she met Charles Walker and began using the name Madam C.J. Walker after their marriage in 1906. Walker began selling her own hair products door to door as an independent hairdresser. Walker then moved to Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania and opened a beauty parlor to train her agents (licensed stylists who earned commission) on the "Walker System.” Not only did this give her the ability the grow her business, but she also was able to hire Black women and help them gain economic independence. Walker was adamant about supporting the Black community. She spoke at conventions, raised money to establish a YMCA branch in Indianapolis, gave lectures alongside other Black leaders of her time, was active in the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP), and much more. In 1910, Walker relocated her business to Indianapolis where she built a factory, hair salon, and beauty school. Her business continued to grow, and at the time of her death, she was believed to be the wealthiest self-made Black woman in America.

Supporting Question

Why does Garrett Morgan’s story still matter?

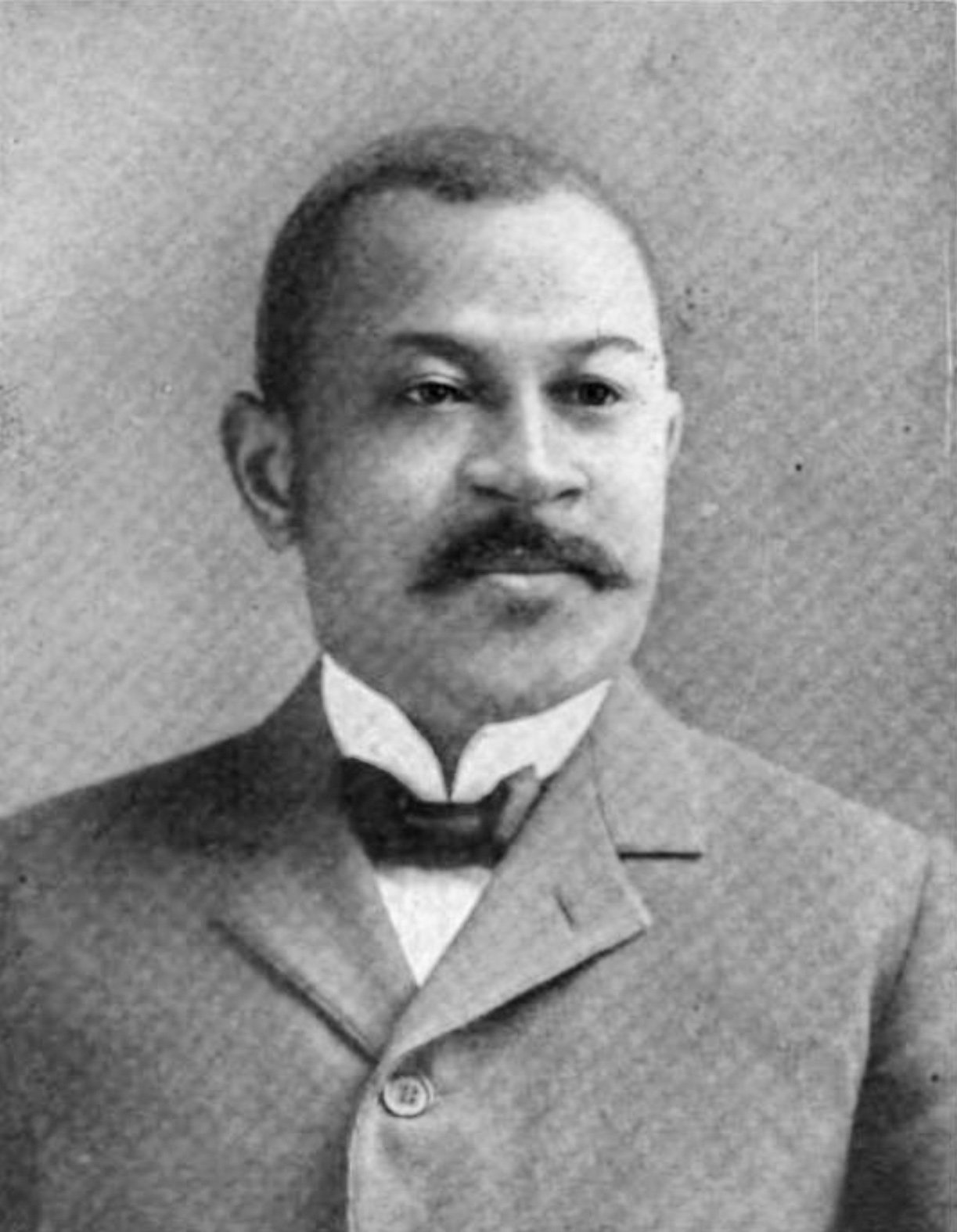

Garrett Morgan (1877-1963)

Short Bio: Garret Morgan is credited with inventing the three-way traffic light, the gas mask, and various hair products. His gas masks (the Morgan Safety Hood) proved to be life saving equipment, and his version of the stop light brought more organization and safety to the road. Born in 1877, Morgan was the seventh of 11 children. His mother, Elizabeth, and Father, Sydney, had both previously been enslaved, but had gained their freedom by the time Morgan was born. He grew up in Paris, Kentucky, working on his family farm. Around the age of 14, Morgan decided to move to Cincinnati for better educational and financial opportunities. Just four years after that, Morgan moved to Cleveland where he picked up a job at a manufacturing company, working around sewing machines.

He took his job seriously and learned all he could about the machines. With Morgan’s knowledge about sewing machines, in 1907, he opened his own sewing machine repair company. Later he and his wife opened a tailor shop where his wife (Mary) sewed clothing and Morgan kept the machines in good condition. This venture also led him to creating a hair straightening cream and establish the G.A. Morgan Hair Refining Co. He used the profits from this company to invest in his own inventions. One of those inventions was the safety hood which he patented in 1914. Though Morgan's safety hood had already saved lives, he had a hard time getting white fire chiefs to buy his product because he was Black, so he hired a white actor to help promote his product. Additionally, In 1923, he also patented his three-way traffic signal, and sold those rights to General Electric for $40,000. Though Morgan’s inventions were obviously important, he still faced discrimination because of his race. However, despite his hardships, he still found ways to support his community and making a lasting impression on the world.

Supporting Question

Why does Sarah Goode’s story still matter?

Sarah E. Goode (1855-1905)

Short Bio: Sarah Elisabeth Goode (1855 - 1950) is one of the first Black women granted a patent in the United States. She was born in Toledo, Ohio. Her mother kept the house and worked with the Ohio Anti-Slavery Society and her father is reported to have worked as a waiter. Around 1870, Goode's family moved to Chicago, where she later married and had children. In 1885, while working at her and her husband’s furniture store, she patented her design for the cabinet bed. This invention made Goode one of the first African American women to receive a U.S. patent. During a time when minoritized and impoverished people often signed over their patents to employers in order to fund the production of their product, Goode was able to maintain ownership of her patent and create and sell the cabinet bed out of her furniture store. She had noticed that with the limited space available in apartments, people needed a functional piece of furniture that could serve various purposes.

Though there is not much public information about Goode, it is recorded that in Thomas J. Calloway and W.E.B. Du Bois' The Exhibit of American Negroes, Goode was one of four women identified from the group of African American inventors featured. In a time where Black people had to fight to be recognized for their societal contributions and women were expected to shrink themselves, Sarah Goode created a needed item that became popular in many homes and secured her place in history while doing so.

Supporting Question

Why does Lonnie Johnson’s story still matter?

Lonnie Johnson(1949)

Short Bio:

Compelling Question: What lessons should we learn from the lives of Black inventors?

-

Summative Performance Task Argument

Students should draw on sources to make informed arguments in a whole class discussion that answers the compelling question, what lessons should we learn from the lives of Black inventors?

-

Summative Performance Task Extension

Students can create a poster or other creative project for a class Black Inventor’s Museum that uses evidence to answer the compelling question, what lessons should we learn from the lives of Black inventors?

-

Taking Informed Action

Students can identify ways that Black inventors are still making change in the present (see Timnit Gebru, etc.) and identify what supports they need to thrive.

Students could investigate whether students from all races are equally represented in advanced STEM classes in their district, and whether the curriculum is culturally responsive and pursues a more just world. They can advocate for change as is necessary.