Sleights of hand: What library patron data is PII (and what isn’t)

Civics of Technology Announcements

New! Technology Audit Curriculum: This activity provides a structured way to surface the ethical dimensions of technology tools. Drawing on four analytic approaches developed through the Civics of Technology project, educators and students can ask disciplined, critical questions that move beyond whether a tool “works” to whether it aligns with their educational values and responsibilities. An audit supports informed judgment about whether to adopt a technology as designed, modify its settings or uses, or reject it altogether. Importantly, this process also positions teachers and students as civic actors who can advocate for more responsible technology practices within classrooms, schools, districts, and communities.

Next Tech Talk: Please join us for our next Tech Talk where we meet to discuss whatever critical tech issues are on people’s minds. It’s a great way to connect, learn from colleagues, and get energized. Our next Tech Talk will be held on Wednesday, February 4th at 8:00 PM Eastern Time. Register here or visit our Events page.

Privacy Week Webinars: On January 22 (note the updated date!) and 29 - see our Privacy page to learn more!

Editors’ Note: This week’s blog is written by Jamie Taylor, one of the presenters for Day 1 of a two-day webinar for Privacy Week taking place on January 22 and January 29. The webinar is organized by Morgan Banville, the Massachusetts Maritime Academy, and the Civics of Technology Project. Visit our Privacy page to learn more and register.

By Jamie Taylor

“PII” stands for “personally identifiable information.” It is information that directly identifies a person: their name (sometimes; if I google my name, I primarily see results for a football player’s partner) or social security number, for example. It has legal definitions, though that definition varies by jurisdiction, and different jurisdictions have more or fewer rights and protections associated with it. Most of us probably know that the European Union has stronger rights and protections than the United States, and that California has state-level rights and protections in addition to federal ones.

You are probably also familiar with some of the artifacts created by these legal rights and protections. Think about all the pop-ups on websites that demand you select which cookies to accept, or click a button to acknowledge that you’ve read the privacy policy, or tell you that if you continue to use the site you have agreed to the policy whether you like it (and have read it) or not. Some of these pop-ups use dark patterns, such as making the button for declining cookies or data collection hard to find, thereby nudging you to consent to more surveillance than you might want. For those of us of a certain age, we remember that these were not always a ubiquitous feature of the internet; they started appearing after the EU passed the General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR) a decade ago, as an easy way for website owners to comply with data regulations.

You will also perhaps have realized how difficult it is to avoid unwanted cookies or data collection completely. A fundamental power imbalance exists between website owners, some of whom are the wealthiest companies and people that have ever existed, and us, the end users. That site has something we want or need, and we can’t have it without agreeing to surveillance. There is often not an equivalent option out in the universe that would give us the thing we want or need without the surveillance. And there is no realistic mechanism for us to negotiate the contract terms for using that website; we can’t have our lawyer contact theirs and get a contract written for us to use Amazon under terms that forbid Amazon from collecting, storing, and reusing a whole slew of data about us.

All this to say, I’ve noticed something about library software and database vendors. They, like their non-library industry peers, do this fancy footwork of language, dark patterns, and coercion. I noticed this after a (successful!) attempt to get EBSCO to change their data retention policies in 2023. When my library went live with EBSCO Discovery Service, a colleague and I discovered that it was collecting search and click information for all logged-in users and then saving it in such a way that it could be reassociated with an individual’s name and other identifying information. Through sheer doggedness, good organizing, and a year of meetings and emails, we won an important victory for library patron privacy – not just for my library, but for every EBSCO customer. EBSCO now only retains that data for 35 days, whereas they previously held onto it for 11 months. You’re welcome.

This sent me down a rabbit hole of investigating exactly what other library vendors are doing with equivalent data. I quickly found – nothing. Nothing comparable, at least, to the information about the 11-month data retention period that EBSCO had been willing to share with me. To the end user (that is, a library patron), the data privacy practices of their primary competitor, Clarivate and its subsidiaries ProQuest, Ex Libris, and Innovative Interfaces (III), is indistinguishable from that of any other commercial website. Clarivate’s data retention period is not available in their documentation; EBSCO’s isn’t either, but I don’t think Clarivate would just tell me if I asked them, like EBSCO did.

Library vendors, especially the biggest ones such as EBSCO and Clarivate, are mostly for-profit companies and many (such Overdrive, or Clarivate before it went public) are owned by private equity. So, I am not surprised that their data surveillance procedures are the same as other types of for-profit companies. I am similarly not surprised that their obfuscation, dark patterns, and reliance on lock-in and a captive audience all work the same as well. EBSCO, Clarivate, Elsevier, OverDrive, and so on all have a profit motive and our data is much too juicy a resource to ignore.

Which brings me back to the issue of PII. The difference I noticed between EBSCO and Clarivate is some fancy footwork with language. I was able to browbeat EBSCO into an improved data retention period because they had, perhaps unwittingly, extended the meaning of PII in ways that have not been done by other vendors. (NB: I am by no means lauding EBSCO or encouraging libraries to subscribe to their products; this is merely illustrative. They have, after all, not opted to decline the industry standard data collection and “notice and choice” approach to it, which is an entirely real choice they could make.)

Library vendors claim that they only collect and retain our data for legitimate business purposes, that it is stored securely, and that (usually) it is anonymized. EBSCO says, for example, as answer to how long they retain our data,

“We retain Personal Information we collect from you where we have an ongoing legitimate business interest or other legal need to do so (for example, to provide you with a service you have requested or to comply with applicable legal, tax or accounting requirements). When we have no further legitimate business interest or legal need to process your Personal Information, we will either delete or anonymize it or, if this is not possible (for example, because your Personal Information has been stored in backup archives), then we will securely store your Personal Information and isolate it from any further processing until deletion is possible.”

A library patron’s only option for exercising control over this data is to delete their account entirely, which is not a realistic option for a patron who wishes to continue to use their library.

“We automatically collect non-Personal Information generated from your use of our Services. We use this non-Personal Information in the aggregate. We do not combine these types of non-Personal Information with Personal Information.”

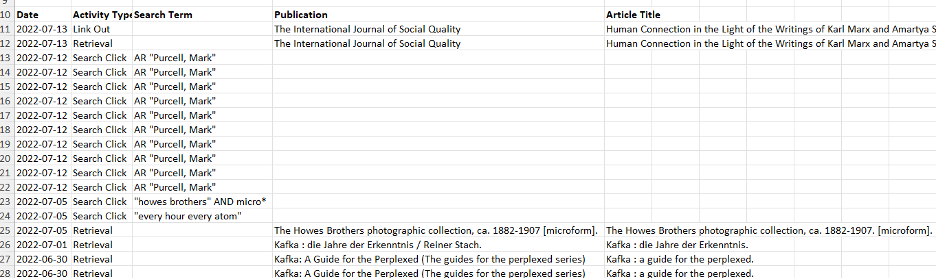

I think this is the search and click data – what you are searching for, reading, and borrowing – that has the 35-day retention period. This data has a common key that can reaggregate it with separately stored PII such as email address, name, or library account number. If you have an EBSCO account, you can easily see that this is the case by submitting a data request within your account. If the two silos of data could not be reassociated, you would not be able to get your data. A past report of my data looked like this:

Screenshot of an excel table showing EBSCO PII data

In the NIST definition, this data would likely be called potential PII, as it can be identifying when combined with other information. The EU's definition specifically says that PII can be directly or indirectly identifying, making a stronger argument that the kind of data EBSCO is talking about here is PII, even though EBSCO has labeled it non-PII. Regardless: despite calling it “non-Personal Information,” EBSCO seems to functionally concede that it is PII, since they place the kind of controls on it that are required by regulations such as the GDPR. As a systems librarian, I abide by the principle that the purpose of a system is what it does.

Here’s the fancy footwork. To my eye, Clarivate and subsidiaries, despite using very similar language in their privacy policies, do not treat this kind of non-PII as if it were PII. Library patrons using Clarivate, ProQuest, Ex Libris, or Innovative software and databases do not have the ability to examine or delete their usage data the way I can with my BSCO data above – Clarivate does not put GDPR-style control of it in library patron hands, as they have determined it to not be subject to those regulations. It seems to me that “PII” is in part a marketing term, in the same way that “AI” is; it does have some central meaning but can be expanded or contracted around the edges to do what the powerful wish it to do.

So: which is it? Is the usage data of these systems PII or not? I consider it to be PII, but I don’t get to make those decisions. The American Library Association thinks that this kind of data should be protected in some way, as Article VII of the ALA’s Library Bill of Rights reads,

“All people, regardless of origin, age, background, or views, possess a right to privacy and confidentiality in their library use. Libraries should advocate for, educate about, and protect people’s privacy, safeguarding all library use data, including personally identifiable information.”

EBSCO's programmatic decisions indicate it is or could be. Clarivate’s say it is not. You probably think this data, about you and created by you and possibly rather sensitive, should be protected, too. And when it is generated by using your library, you might think it automatically is. But libraries and librarians do not have the protections of confidentiality that, say, doctors, lawyers, and clergy do. Doctors, lawyers, and clergy know an awful lot of your secrets and sensitive information. So do libraries and their workers. Your school records are private, subject to FERPA and other laws. But those laws do not cover your library use, even in connection to coursework or when the library is part of a school. When libraries buy software that is hosted in the cloud (which is just someone else’s computer) or subscribe to databases, your use data leaves the library entirely, putting us at the mercy of these linguistic and legal maneuverings.

And I am sorry to report that the best we can do, often, to maintain the kind of privacy library we have long told readers they can expect is to browbeat vendors into acting right, and that it only rarely works.